Introduction to Linear Partial Differential Equations*

This is the note from MNE8108 Engineering Methods in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, CityU (semester A, 2025)

Contents mostly From Advanced Calculus for Applications by Francis Begnaud Hildebrand

Partial differential equations definition

Motivation

Why do we study partial deferential equations (PDEs) and analytic solutions?

We are interested in PDEs because most of mathematical physics is described by such equations. For example, fluids dynamics (and more generally continuous media dynamics), electromagnetic theory, quantum mechanics and etc.

Typically, a given PDE will only be accessible to numerical solution and analytic solutions in a practical or research scenario are often impossible. However, it is vital to understand the general theory in order to conduct a sensible investigation. For example, we may need to understand what type of PDE we have to ensure the numerical solution is valid. Indeed, certain types of equations need appropriate boundary conditions; without a knowledge of the general theory it is possible that the problem may be ill-posed and the solution is erroneous.

Definition

Definition: Partial derivatives

Partial derivatives: The differential (or differential form) of a function

where the partial derivatives are defined by

A partial differential equation (PDE) is an equation for some quantity

Linear

The order of the PDE is the order of the highest (partial) differential coefficient in the equation.

As with ordinary differential equations (ODEs) it is important to be able to distinguish between linear and nonlinear equations.

A linear equation is one in which the equation and any boundary or initial conditions do not include any product of the dependent variables or their derivatives; an equation that is not linear is a nonlinear equation.

Principle of superposition: A linear equation has the useful property that if

Example of Linear PDEs: Wave Equations

Waves on a string, sound waves, waves on stretch membranes, electromagnetic waves, etc.

or more generally

where

Example of Linear PDEs: Heat Conduction

or more generally

or even

where

First Order Linear PDE: Method of Characteristic

We consider linear first order partial differential equation in two independent variables:

where

The key to the solution of the equation (2.1) is to find a change of variables (or a change of coordinates)

which transforms (2.1) into the simpler equation

where

We shall define this transformation so that it is one-to-one, at least for all

for

We substitute these into equation (2.1) to obtain

We can rearrange this as

This is close to the form of equation (2.1) if we can choose

Provided that

Then the equation is

Suppose we can define a new variable (or coordinate)

implies that

Equation (2.5) is called the characteristic equation of the linear equation (2.1). Its solution can be written in the form

So, we have made the coefficient of

Then

and we have already assumed this non-zero.

Now we see from equation (2.4) that this change of variables,

transforms equation (2.1) to

where

Finally, restricting the variables to a set in which

which is in the form of (2.3) with

The point of this transformation is that we can solve equation (2.3). Think of

as a linear first order ordinary differential equation in

Now we integrate with respect to

in which

We obtain the general form of the original equation by substituting back

Example: The method of characteristic

Example: Consider the constant coefficient equation

where

with general solution defined by the equation

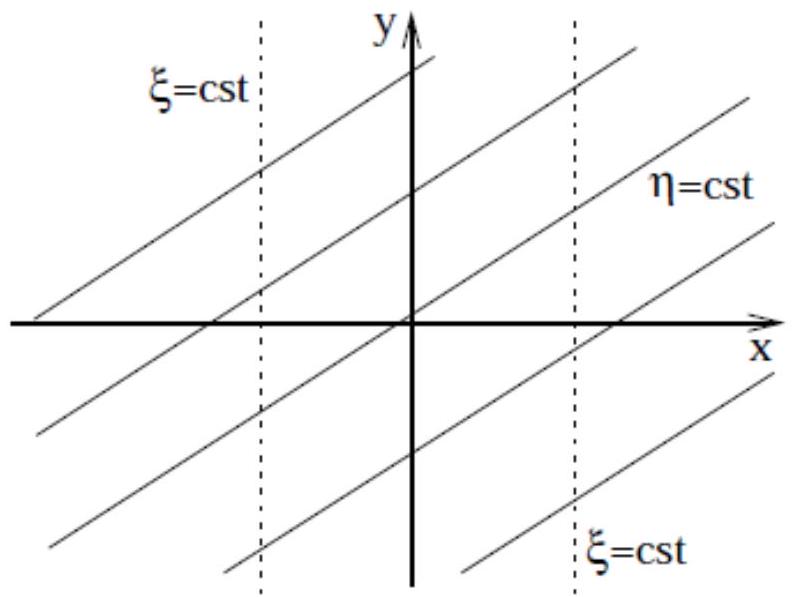

So the characteristics of the PDE are the straight line graphs of

Using the substitution we find the equation transforms to

The integrating factor method gives

and integrating with respect to

where

and in terms of

Example 1: More specific Linear first order PDE

Consider

The characteristic equation is

and the characteristics are the straight line graphs

(We can see that an

This gives the solution

where

Suppose we specify values of

Then we need

and putting

This determines

We have determined the unique solution of the PDE with

to give the unique solution

satisfying

However, not every curve in the plane can be used to determine

Now we must choose

This requires

Last, we consider again

Now we must choose

This requires

Depending on the initial conditions, the PDE has one unique solution, no solution at all or an infinite number or solutions. The difference is that the

Example 2

Characteristics:

So, take

Finally the general solution is,

This figure presents the characteristic curves given by

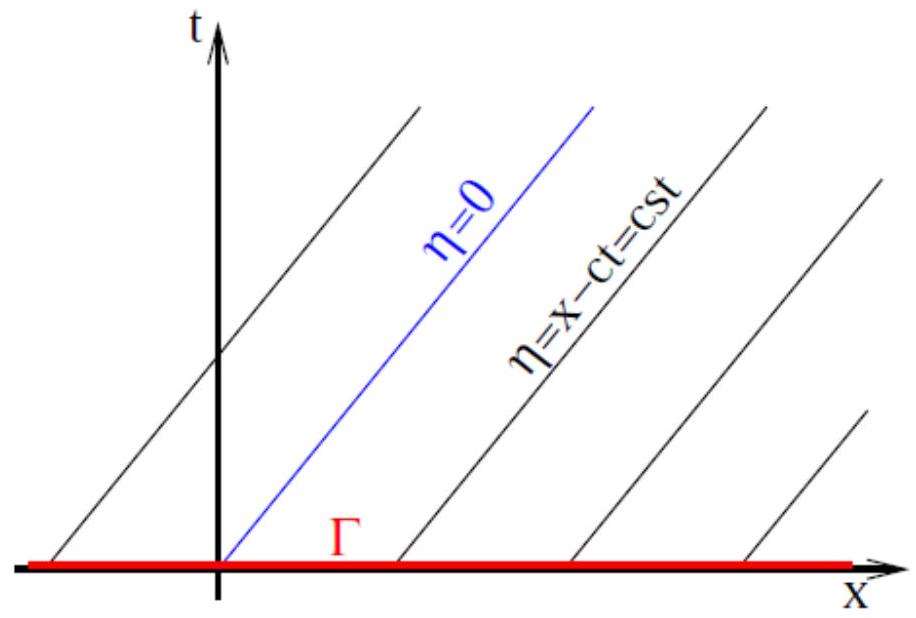

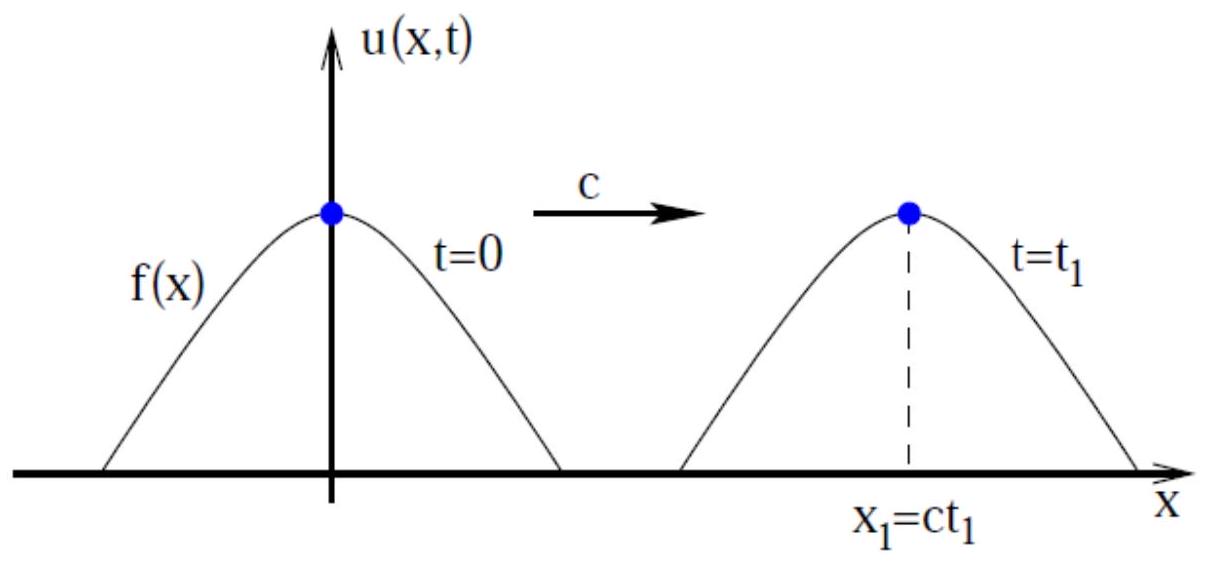

Application: Linear Waves

If

The solution of the equation of characteristics,

Note that

Second Order Linear PDE

Consider a general second order linear equation in two independent variables

Recall, for a first order linear and semilinear equation,

For the second order equation, can we also transform the variables from

As before we compute chain rule derivations

The equation becomes

where

Equation (3.1) can be simplified if we can choose

then we can write

Now consider the quadratic equation Vanish the item:

whose solution is given by

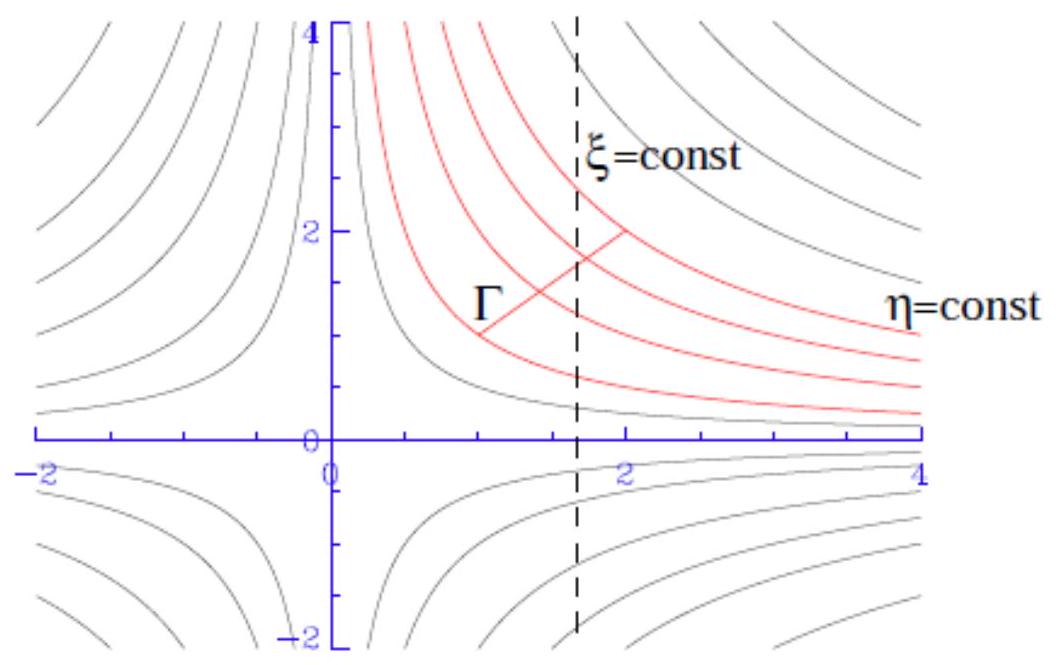

- If the discriminant

:

equation (3.2) has two distinct roots; so, we can make both coefficients

Then, using

Furthermore, if the discriminant

then

and make use of (3.3) to find that this characteristics satisfy

Similarly we find that the characteristic curves described by

- If the discriminant

:

equation (3.2) has one unique root and if we take this root for

To get

so that

Classification of

- If

we can apply the change of variable to transform the original PDE to

In this case the equation is said to be hyperbolic and has two families of characteristics given by equation (3.4) and equation (3.5).

- If

, a suitable choice for still simplifies the PDE, but now we can choose arbitrarily - provided and are independent - and the equation reduces to the form

The equation is said to be parabolic and has only one family of characteristics given by equation (3.6).

- If

we can again apply the change of variables to simplify the equation but now this functions will be complex conjugate. To keep the transformation real, we apply a further change of variables via

so, the equation can be reduced to

In this case the equation is said to be elliptic and has no real characteristics.

Example

- The wave equation,

is hyperbolic (

- The diffusion (heat conduction) equation,

is parabolic (

- Laplace's equation,

is elliptic

Example 1: Reduce to the canonical form

Here

We can choose

and the equation becomes

This has solution

where