Bearing

Introduction [1,2]

Distance measurements are not the only geometrically pertinent quantities that can be used in formation maintenance. Agents in a formation framework can have other sensing capabilities and exploiting one or more of the capabilities can contribute to shape control.

Another form of such a geometric quantity is bearing, and such a quantity, in conjunction with distance, can contribute in maintaining the shape of a formation. Bearings along with distances have been used for navigation of robot applications by using the leaderfollower approach while maintaining a desired formation.

A bearing is the angle between the

- By “trigonometric direction” is meant the counterclockwise rotation direction around a trigonometric circle.

- By a node’s local coordinate system is meant a coordinate system which is chosen by each node based on some criteria, e.g., the coordinates are referenced to a known location in the immediate area, or the longer side of a node is chosen to be the x -axis of the local coordinate system, and so forth. Two local coordinate systems may not always line up on the same map.

If two nodes

two benefits of bearing measurements:

- A formation based on angles can be scaled up more easily compared to formations using only distance measurements since bearings are essentially angle measurements. A bearing rigid formation based on all bearings with an additional measurement of one distance measurement maintains its shape. If we reserve the single distance measurement between the

and the leader agents, then translation, rotation and scaling of the formation can easily be managed by these two agents. - Bearing-based rigidity along with a single distance measurement not only provides local uniqueness that is useful for formation shape, but also provides global uniqueness that plays a role in multi-agent localisation. This property gives us an unambiguous relative positions of agents with respect to each other.

2D Bearing Rigidity [1,2]

Parallel Drawings

Definition: plane configuration

A plane configuration is a collection of geometric objects such as points, line segments and circular arcs in the plane, together with constraints on and between these objects.

Definition: parallel drawings

Two formations on the same graph are parallel drawings if corresponding edges are parallel.

By a 2D formation at

Given a formation

Each such constraint is called a direction constraint

Proposition 1

A bearing constraint can be written as a direction constraint.

Details of Proof

A bearing constraint for node

and similarly the bearing constraint for node

where

By a trajectory of

and for node

Next, let us consider the vector

and for node

Thus

For every link with a bearing constraint in the point formation, it is now straightforward to write

Q.E.D.

This gives a system of

Parallel Rigidity

Given a formation

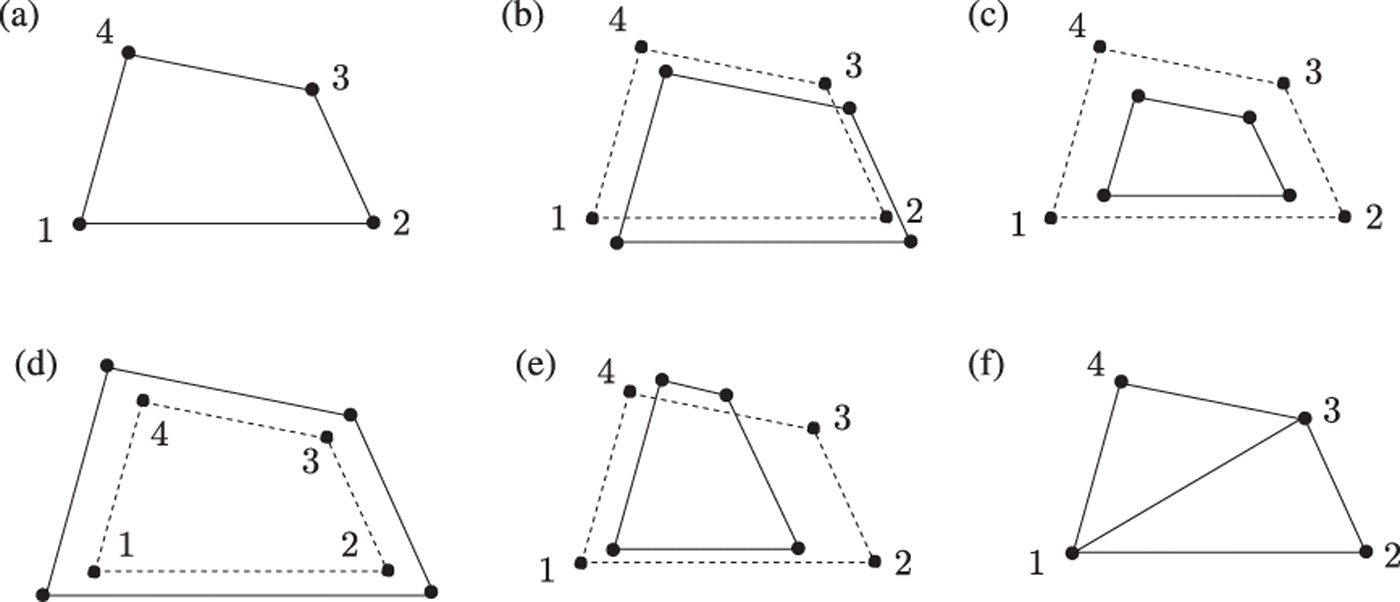

For example, Figure 1(b) shows a translation of the formation in Figure 1(a); and Figure 1(c) and (d) are uniform scaling of the formation in Figure 1(a). In particular, Figure 1(c) is a uniform contraction and Figure 1(d) is an uniform expansion. Figure 1(e) shows a non-trivial parallel formation of Figure 1(a), because the formation in Figure 1(e) cannot be obtained from the formation in Figure 1(a) by translation or uniform scaling although all the corresponding links in these two formations are parallel to each other.

Definition: parallel rigid motion

A parallel rigid motion is a trajectory along which point formations contained in this trajectory are translations or dilations of each other.

Two point formations

Definition: parallel rigid

A formation

If parallel rigid motions are the only possible trajectories then the formation is called parallel rigid, otherwise parallel flexible.

For example, the formation in Figure 1(a) is flexible. On the other hand, the formation in Figure 1(f), which is obtained from the formation in Figure 1(a) by inserting an extra link

Taking the derivative of

These equations can be rewritten in matrix form as

where

It is shown that any statement for a point formation of distances can be given for the same point formation of directions where distances are switched with directions. The isomorphism goes down the pairs of columns for each vertex, turning all the vectors by

Theorem 1

A graph

; - For all

, where is the number of vertices that are end-vertices of the edges in ;

For frameworks using pure distance information, the conditions for global rigidity are stronger than those for rigidity of formation with distance constraints.

For frameworks in

Theorem 2

If

Details of Proof

Suppose that

Conversely, suppose that

More generally, nodes are not confined to use their sensing and communication links for measuring distances only. We can exploit such a possibility to generate point formation that is not only locally unique but also globally unique with as few links as a minimally rigid formation.

For formations with combined distance-bearing constraints, there is the following combinatorial characterization of parallel rigidity.

Theorem 3: generically parallel rigid

With

; - For all subsets

of vertices: ; - For all subsets

of at least vertices: ; - For all subsets

of at least vertices: .

TODO Proof

B. Servatius, W. Whiteley, “Constraining plane configurations in Computer Aided Design: Combinatorics of directions and lengths,” 1995, preprint, York University, North York, Ontario.

The conditions for distance-direction constraints are closely related to the conditions for parallel rigidity for distance-bearing constraints since bearing constraints can be written as direction constraints as stated in Proposition 1.

A point formation using direction-distance constraints can be unique up to translation. This will require

- An independent set of

distances plus any single direction is an appropriate set of constraints; - An independent set of

directions plus any single distance is an appropriate set of constraints; - A spanning tree, used once for distances and a second time for directions, is an appropriate set of

constraints.

A tree is a graph in which any two vertices are connected by exactly one path. Given a connected, undirected graph, a spanning tree of that graph is a subgraph which is a tree and connects all the vertices together.

Are these sufficient? Even for distances, we know that these conditions are not sufficient for special positions of the points. However, by Laman’s Theorem, they are sufficient for distances on ‘generic configurations’. The most we can expect is that these expanded conditions are also sufficient for ‘generic configurations’. We replace the entries for the points

This characterization also covers the distance-bearing combinations that permit more than one distance. Note that this is the criterion for rigidity up to translation, not for global rigidity, if there are multiple distance constraints. It is rigidity up to translation since rotations are not allowed because of bearing constraints. We suspect that it is probably the criterion for global rigidity, up to translation, if there are enough bearing constraints. Under this assumption, and assuming that angle of arrival is measured in trigonometric direction, we have a conjecture for global rigidity.

Conjecture 1 (in 2007)

Provided that the underlying graph constructed with the links representing bearing constraints form at least a spanning tree, then for generic formations, rigidity up to translation is equivalent to global rigidity of the formation.

Bearing Rigidity

Bearing constraints in mobile formations have

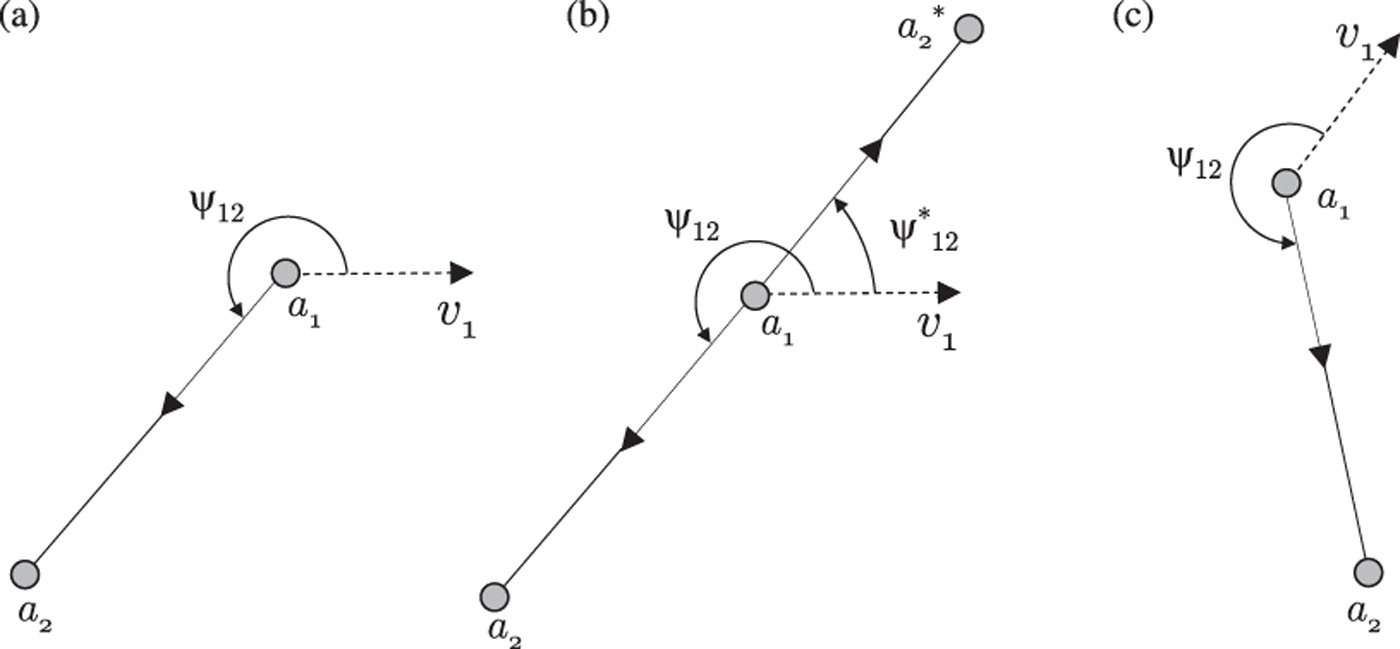

- Bearing constraint is more stringent than direction constraint. For example, assume that

is fixed in -space as shown in Figure 2(a) and has a bearing constraint with . Note that, direction constraint is satisfied by both and as shown in Figure 2(b), where one is obtained by a flip of the other w.r.t. . Thus, a direction constraint can be thought as a necessary condition of a bearing constraint. For maintaining the shape of a mobile formation, where only continuous motions of agents are feasible, flip ambiguity is avoided, and thus, we can make use of parallel drawings for the analysis and design of rigid formations that make use of bearing measurements. - Direction constraints, in the context of parallel drawings studied in computer-aided design, are measured w.r.t. a fixed global reference frame, whereas bearing constraints in mobile formations are measured w.r.t. the heading of leader agents. This selection of reference frame renders bearing constraints convenient for mobile formations, because follower agents act to satisfy bearing constraints as their leaders move (and possibly change their headings), hence preserving the shape of the overall formation. For example, if a1 changes its heading direction as shown in Figure 2(c), then

has to change its position to satisfy the bearing constraint, which results in shape maintenance. This aspect makes the application of bearing rigidity in formation navigation different than the application of bearing rigidity in framework localisation.

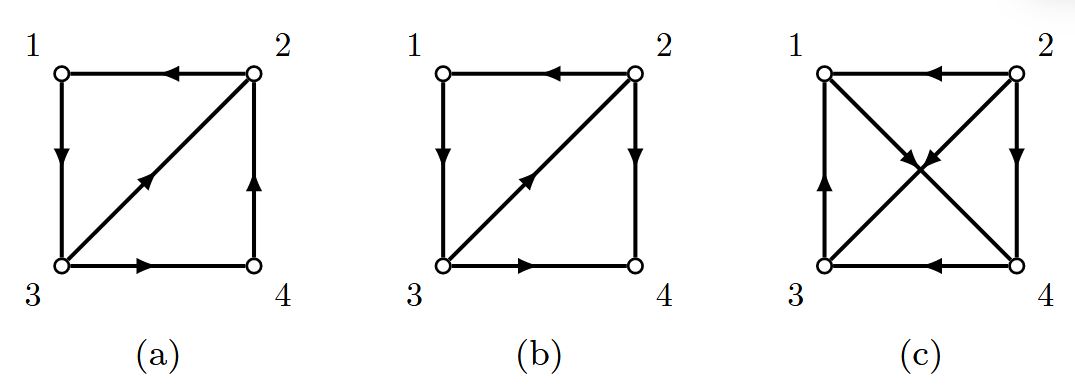

We can state the conditions for bearing rigidity for a digraph as follows:

Definition: Bearing Rigidity

Given a digraph

; - For all

, where is the number of vertices that are end-vertices of the edges in ; is constraint consistent.

This test provides a combinatorial formation analysis method to test rigidity for a given formation. In the context of navigating formations of mobile agents, we will call the formations satisfying the

From a formation synthesis (design) point-of-view, there is a Henneberg type method to construct bearing rigid formations.

Bearing-based Henneberg construction

A Henneberg-type construction is a technique for growing rigid digraphs starting from a single edge in 2-space. One of the following operations is applied (when applicable) at each step in the procedure. The resulting graphs are provably rigid.

- Directed

-valent vertex addition: Given a digraph where , a vertex of in-degree is inserted into by adding the edges and . - Directed

-valent vertex deletion: Given a digraph where , a vertex of in-degree with the edges and is deleted from . - Directed

-valent vertex addition: Given a digraph where , a vertex of in-degree and out-degree is inserted into by deleting the edge and adding the edges and . This operation is also known as edge splitting operation. - Directed

-valent vertex deletion: Given a digraph where , the vertex of in-degree and out-degree is removed from by deleting the edges and and inserting one of the pairs in . - Edge reversal: Given a digraph

where , an edge in is replaced by .

A minimally bearing rigid formation in 2-space has

- two-leader formation structure, in which there is an agent (

leader) that has DoF, and another agent ( leader) with DoF such that these agents are neighbours. For bearing rigid formations, we prefer the term -leader formation because the agent that has DoF in a bearing rigid formation has the control of scaling on the entire formation, which makes it act like a leader rather than a follower. Moreover, by changing its bearing to the leader, the leader can change the orientation of the entire formation. - leader-remote follower structure, in which the agent with

DoF is not a neighbour of the agent with DoF. - three-coleaders structure. This is a formation structure in which there are three agents

(called the coleaders) with DoF each. Three-coleader structure can further be classified within itself depending on the neighbourhood relations of coleaders.

In this article, the formations we study are of a two-leader variety.

Scalable bearing rigid formations

We need to address one more issue on bearing rigidity before we proceed any further. Bearing rigidity, as it is defined above, is based on

However, unless there is a proper action, note that all bearing constraints will still be satisfied if a formation expands or contracts. In other words, we have no control over the scale of a formation in a bearing rigid formation. We need at least one distance measurement to be able to fix the scale of a formation, which results in ‘scalable bearing rigid formations’.

A scalable bearing rigid formation is obtained from a bearing rigid formation of

In summary, the

Directed Rigidity

Acyclic formations

First, we give some terminology.

- A directed edge is written with an ordered pair of end-vertices

representing an edge directed from to and drawn with an arrow from to , that is from the source to the sink. - The number of edges directed into a given vertex i in a digraph

is called the in-degree of the vertex and is denoted by . The number of edges directed out from a given vertex in a digraph is called the out-degree of the vertex and is denoted by . - The out-neighborhood

of a vertex is , and the in-neighborhood of a vertex is . The union of out-neighborhood and in-neighborhood is the set of neighbors of , i.e., the (open) neighborhood of , . When is also included, it is the closed neighborhood of .

Definition: directed path

A directed path is a non-empty digraph

Definition: cycle

A closed directed path, with no repeated vertices other than the starting and ending vertices is called a (directed) cycle and is denoted by

Definition: cycle graph & cyclic graph & acyclic graph

- A cycle graph is a graph on

vertices containing a single cycle through all vertices. - A cyclic graph is a graph containing at least one cycle.

- A graph that is not cyclic is said to be acyclic.

Care should be taken with cyclic formations, which can lead to unstable behaviours in the presence of measurement errors if the agents are not allowed to communicate. Further, we show that bearing rigid formations with coleader structure and leader-remote follower structure occur only in cyclic formations. Therefore, we avoid such structures in shape control.

Another disadvantage of coleader formations in bearing rigid formations is that they not only require a coordinated motion of three coleaders, but also require a consensus on the heading of all three coleaders. We have the following two theorems.

Theorem 0.1

For a digraph

is minimally bearing rigid and acyclic; is constructed from a single edge by a sequence of directed vertex additions has two-leader architecture, and is acyclic with all other vertices having in-degree exactly .

Details of Proof

: Minimally directed bearing rigid digraphs are constraint consistent and they have . We are given that there are no cycles in the digraph. Therefore, the digraph represents a partial order between vertices. The partial order can be made into a complete order. The smallest element in the order is the leader, and the next smallest is the leader, and this will be our target edge for the directed Henneberg sequence. Assume that there are more than vertices. The maximal element has all edges in so it has in-degree . Overall, since each edge is directed: . However, the two initial vertices have a total in-degree of , so on all other vertices . We also know that all vertices have , so we conclude that all other vertices have . Take the maximal vertex in the linear order. All edges are in-directed, so the overall valence is . We can apply -valent vertex deletion to get a smaller directed bearing rigid acyclic graph, with the induced linear order. We continue with this until there are only the leader and the leader. Reversing this sequence gives the desired construction. is equivalent to : This is immediate, as the initial edge is the first leader-second leader edge, and the valence assumption is equivalent to the count of .

Theorem 0.2

Minimal bearing rigid formations with coleader structure or leader-remote follower structure occur only in cyclic formations.

Proof: Suppose that coleader structures and leader-remote follower structures occur in acyclic formations too. Acyclic formations can be built by using only

In short, formation control using bearing measurements is straightforward if the underlying directed graph is acyclic, since it is based on a partial ordering of agents due to an absence of cycles. Acyclic bearing rigid formations can be constructed using a sequence of directed vertex additions, and they have two-leader architecture. Therefore, we will base the rest of this article on acyclic bearing rigid formations. In particular, we will make use of scalable bearing rigid formations. Construction of such formations starts with a double edge between the

Any ordinary node in a framework with directed bearing links needs to have at least

However, we insert the implicit links among anchor nodes to obtain the grounded graph. Furthermore, the existence of one anchor node rules out translation. If there is only one anchor node, then scaling is still allowed. This means that

A point formation with directed bearing constraints is called directed parallel rigid if all directed parallel point formations are trivially parallel. There are a number of issues that must be addressed in the localization of frameworks with directed links. We identify three key layers as follows:

- Parallel rigidity of the underlying undirected formation;

- Directed parallel rigidity of the formation;

- Convergence and the quality of initial position estimates in the framework

If underlying undirected formation is non-rigid, then directed formation cannot be rigid. Thus, undirected rigidity is a necessary condition for directed rigidity. On the other hand, when we associate a direction to each link in a rigid undirected formation, directed parallel rigidity is not necessarily guaranteed, because an in-degree of a node may be set to

Theorem 4

Given a grounded digraph

; - For all

, where is the number of vertices that are end-vertices of the edges in ; is -directed.

Bearing Rigidity in Arbitary Dimensions [4]

Basic Conceptions

Define:

Note the unit vector

We now introduce an important orthogonal projection operator that will be widely used in this paper. For any nonzero vector

For notational simplicity, denote

is an orthogonal projection matrix which geometrically projects any vector onto the orthogonal compliment of - It can be verified that

, and is positive semi-definite. and the eigenvalues of are . - Any two unit vectors

satisfy . - For any nonzero vectors

where , the matrix is nonsingular if and only if at least two of are not colinear - For any two nonzero vectors

, if is the angle between them so that , then - If

is a unit vector, then where

is the skew-symmetric matrix associated with

Lemma 1: parallel in

Two nonzero vectors

Proof: The result follows from

Most existing works, like the last section, use the notion of normal vectors to describe parallel vectors in

. Specifically, given a nonzero vector , denote as a nonzero normal vector satisfying . Then any vector is parallel to if and only if . This approach is applicable to 2D cases but difficult to extend to arbitrary dimensions. Moreover, it is straightforward to prove that in the use of the orthogonal projection operator is equivalent to the use of normal vectors based on the fact that

Fundamental Concepts about Bearing Rigidity

Now ready to define the fundamental concepts in bearing rigidity. These concepts are defined analogously to those in the distance rigidity theory.

Definition: Bearing Equivalency

Frameworks

Definition: Bearing Congruency

Frameworks

By definition, bearing congruency implies bearing equivalency. The converse, however, is not true, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Definition: Global Bearing Rigidity

A framework

By definition, global bearing rigidity implies bearing rigidity. As will be shown later, the converse is also true.

We next define infinitesimal bearing rigidity, which is one of the most important concepts in the bearing rigidity theory. Consider an arbitrary orientation of the graph

as the edge vector and the bearing for the

The bearing function describes all the bearings in the framework. The bearing rigidity matrix is defined as the Jacobian of the bearing rigidity function

Let

- The term infinitesimal is due to the fact that the bearing rigidity matrix is the first-order derivative (the Jacobian) of the bearing vectors w.r.t. the positions of the nodes.

- An infinitesimal bearing motion of a framework is a motion of some nodes that preserves all of the bearings. All of the infinitesimal bearing motions of a framework form the null space of the bearing rigidity matrix

Distance preserving motions of a framework include rigid-body translations and rotations, whereas bearing preserving motions of a framework include translations and scalings.

An infinitesimal bearing motion is called trivial if it corresponds to a translation and a scaling of the entire framework.

Definition: Infinitesimal Bearing Rigidity

A framework is infinitesimally bearing rigid if all the infinitesimal bearing motions are trivial.

One important property of an infinitesimally bearing rigid framework is that its shape can be uniquely determined by the inter-neighbor bearings.

An alternative necessary and sufficient condition for infinitesimal bearing rigidity is based on a special matrix termed the bearing Laplacian. [5,6]

Definition: Bearing Laplacian of Networks

Given the framework

where

The bearing Laplacian of a framework can be viewed as a weighted graph Laplacian matrix with weights that are matrices, which describes both the underlying graph and the interneighbor bearings of the framework. Thus, the bearing Laplacian describes not only the topological structure of the framework but the values of the edge bearings.

For a framework with an undirected graph, the bearing Laplacian has the same rank and null space as the bearing rigidity matrix. When the underlying graph is directed, the bearing Laplacian and the bearing rigidity matrix may have different ranks and null spaces (See Bearing Persistence part for details). Compared to the bearing rigidity matrix, the bearing Laplacian is more convenient to use because it is symmetric and positive semidefinite for undirected graphs. Here is more specific:

Lemma 2

For a framework

is symmetric positive semi-definite; and ; and if and only if is infinitesimally bearing rigid.

Details of Proof

Assign an arbitrary orientation to each undirected edge and label the edge vectors and bearings for the directed edges as

Note

Since the nodes in the framework are partitioned into anchors and followers, it will be useful to partition the corresponding bearing Laplacian as

where

Lemma 3

For any framework

Details of Proof

For any nonzero

Up to this point, we have introduced all the fundamental concepts in the bearing rigidity theory. We next explore the properties of these concepts. We first derive a useful expression for the bearing rigidity matrix.

Relationship among types of bearing rigidity

Lemma 4

The bearing rigidity matrix

Details of Proof

It follows from

As a result,

Q.E.D.

The expression

Lemma 5

A framework

.

Details of Proof

- It's clear that

- Since

, we have and hence . - The inequality

follows immediately from .

For any undirected graph

Theorem 5: bearing equivalent & bearing congruent

Two frameworks

- bearing equivalent if and only if

, - bearing congruent if and only if

.

Details of Proof

Since

Therefore, by Definition of bearing equivalent, the two frameworks are bearing equivalent if and only if

Since any infinitesimal motion

We next give a useful lemma and then prove the necessary and sufficient condition for global bearing rigidity.

Lemma 6

A framework

.

Details of Proof

- The result that

and can be proved similarly as Lemma 5. - For any

, we have . As a result, is bearing congruent to by Theorem 5. Since bearing congruency implies bearing equivalency, we further know and hence . Therefore, any in is also in . - Since

have the same column number, it follows immediately that .

Theorem 6: Condition for Global Bearing Rigidity

A framework

Details of Proof

- (Necessity) Suppose the framework

is globally bearing rigid. We next show that . For any , we have . As a result, is bearing equivalent to according to Theorem 5. Since is globally bearing rigid, it follows that is also bearing congruent to , which means . Therefore, any in is in and thus . Since as shown in Lemma 6, we have . - (Sufficiency) Suppose

. Any framework that is bearing equivalent to satisfies . It then follows from that , which means is also bearing congruent to . As a result, is globally bearing rigid. - Because

and have the same column number, it follows immediately that if and only if .

The following result shows that bearing rigidity and global bearing rigidity are equivalent notions.

Theorem 7: Condition for Bearing Rigidity

A framework

Details of Proof

By definition, global bearing rigidity implies bearing rigidity. We next prove the converse is also true. Suppose the framework

where

We next give the necessary and sufficient condition for infinitesimal bearing rigidity.

Theorem 8: Condition for Infinitesimal Bearing Rigidity (Algebraic property)

For a framework

is infinitesimally bearing rigid; ; , where is the centroid of .

Details of Proof

- Lemma 5 shows

. Observe and correspond to a rigid-body translation and a scaling of the framework, respectively. The stated condition directly follows from Definition of infinitesimally bearing rigid. - Note also that

is an orthogonal basis for .

The special cases of

The following result characterizes the relationship between infinitesimal bearing rigidity and global bearing rigidity.

Theorem 9

Infinitesimal bearing rigidity implies global bearing rigidity.

Details of Proof

Infinitesimal bearing rigidity implies

The converse of Theorem 9 is not true, i.e., global bearing rigidity does not imply infinitesimal bearing rigidity. For example, the collinear framework as shown in Figure 5(a) is globally bearing rigid but not infinitesimally bearing rigid.

We have at this point discussed three notions of bearing rigidity:

- bearing rigidity,

- global bearing rigidity,

- infinitesimal bearing rigidity

According to Theorem 7 and Theorem 9, the relationship between the three kinds of bearing rigidity can be summarized as below:

We next explore two important properties of infinitesimal bearing rigidity.

More about infinitesimal bearing rigidity

Geometric Property

The following theorem shows that infinitesimal bearing rigidity can uniquely determine the shape of a framework.

Theorem 10: Unique Shape (Geometric Property)

An infinitesimally bearing rigid framework can be uniquely determined up to a translational and a scaling factor.

Details of Proof

Suppose

where

Since

Property: Invariant to Dimension

The following theorem shows that if a framework is infinitesimally bearing rigid in a lower dimension, it is still infinitesimally bearing rigid when evaluated in a higher dimensional space.

Theorem 11: Invariance to Dimension

Infinitesimal bearing rigidity is invariant to space dimensions.

Details of Proof

Consider a framework

and consequently

- Consider an oriented graph and write the bearings of

and as and , respectively. Since is obtained from by lifting the dimension, without loss of generality, assume where the zero vector is -dimensional. Then

- The bearing rigidity matrix of

is where

Permutate the rows of

Since the permutation of the rows does not change the matrix rank, we have

It can be easily verified using the above equation that

Figure. 4 shows examples of non-infinitesimal bearing rigid frameworks. The frameworks in Figure. 4 are not infinitesimally bearing rigid because there exist non-trivial infinitesimal bearing motions (see, for example, the red arrows). Figure. 5 shows some two- and three-dimensional infinitesimally bearing rigid frameworks. It can be verified that each of the frameworks satisfies

Next, we show that the bearing rigidity of a framework is a generic property that is critically determined by the underlying graph rather than the configuration. We first define the following notion.

Generic Bearing Rigidity [7]

Generic Bearing Rigidity of Graphs

Definition: Generically Bearing Rigid Graphs

A graph

Generically bearing rigid graphs have the following properties.

Lemma 7: Density of Generically Bearing Rigid Graphs

If

Details of Proof

Let

For the sake of completeness, we next present an elementary proof of the density of bearing rigid frameworks. Since

When

If a graph is not generically bearing rigid, there does not exist any configuration such that the framework is infinitesimally bearing rigid. This is implied by the definition of generic bearing rigidity.

- See Figure 7(a) for an illustration. If a graph is generically bearing rigid, the corresponding frameworks are infinitesimally bearing rigid for all configurations except some special ones that form a set of measure zero. This is implied by Lemma 7.

- See Figure 7(b) for an illustration. If a framework is not infinitesimally bearing rigid but its graph is generically bearing rigid, then there always exists a sufficiently small perturbation of the configuration that can make the framework infinitesimally bearing rigid.

Construction of Generically Bearing Rigid Graphs

We have shown that the key to construct infinitesimally bearing rigid frameworks is to construct generically bearing rigid graphs. In this section, we address how to construct generically bearing rigid graphs.

Theorem 12: Generic Bearing Rigidity of Laman Graphs

If

TODO: Details of proof are in the Section IV of Laman graphs are generically bearing rigid in arbitrary dimensions

Theorem 12 indicates that a framework with a Laman graph is infinitesimally bearing rigid for almost all configurations in

The next result shows that adding edges to a Laman graph preserves generic bearing rigidity.

Corollary 12-1

If

Details of Proof

Lemma 10

If

The proof is straightforward.

Lemma 11

Given a graph

Proof:

Since

Proof of Corollary 12-1:

If

:::

While Theorem 12 indicates that Laman graphs are generically bearing rigid, a natural question that follows is whether generically bearing rigid graphs are also Laman. The answer may be negative. A counterexample is given in Figure 9.

The cyclic graph in this example is generically bearing rigid in

This example may be counterintuitive because it shows that a framework is not infinitesimally bearing rigid in a lower dimension yet another framework with the same underlying graph is infinitesimally bearing rigid in a higher dimension. This phenomenon may also be explained by the number of independent constraints posed by a bearing. In particular, in order to ensure the cyclic framework to be infinitesimally bearing rigid in

As indicated by the example in Figure 9, not all generically bearing rigid graphs are Laman or contain Laman spanning subgraphs. However, if we restrict to

Theorem 13

A graph

Details of Proof

The sufficiency follows from Theorem 12 and Corollary 12-1. To prove necessity, we need some notions in the distance rigidity theory. Since

Now we consider two cases. In the first case where

Connections to Distance Rigidity Theory

The bearing rigidity theory and the distance rigidity theory study similar problems of whether the shape of a framework can be uniquely determined by the inter-neighbor bearings and inter-neighbor distances, respectively. It is meaningful to study the connections between the two rigidity theories. The following theorem establishes the equivalence between infinitesimal bearing and distance rigidity in

Theorem 14

In

Details of Proof

To prove Theorem 14, we first prove the following result which indicates that the bearing rigidity matrix always has the same rank as the distance rigidity matrix for any framework in

Proposition 2

For any framework

Proof: Consider an oriented graph and write the bearings of the framework as

The matrix

Note the distance rigidity matrix can be expressed as

Since

Now it comes to proving Theorem 14: By Theorem 8, a framework

Remarks:

- Theorem 14 cannot be generalized to

or higher dimensions. For example, the 3D cubic and hexagonal pyramid frameworks in Figure 6(c), (d) are infinitesimally bearing rigid but not distance rigid. In particular, the rank of the distance rigidity matrices of the two frameworks are and , respectively, whereas the required ranks for infinitesimal distance rigidity are and , respectively. - Theorem 14 suggests that we can determine the infinitesimal distance rigidity of a framework by examining its infinitesimal bearing rigidity. For example, it may be tricky to see the frameworks in Figure 5 (c), (d) are not infinitesimally distance rigid, but it is obvious to see the non-trivial infinitesimal bearing motions and conclude they are not infinitesimally bearing rigid.

An immediate corollary of Theorem 14 describes the relationship between infinitesimal bearing motions and infinitesimal distance motions of frameworks in

Corollary 14-1

The vector

Details of Proof

It immediately follows from

Given a framework in

To end this section, we briefly compare the proposed bearing rigidity theory with the well-known distance rigidity theory. In the distance rigidity theory, there are three kinds of rigidity: (i) distance rigidity, (ii) global distance rigidity, (iii) infinitesimal distance rigidity.

The relationship between them is (ii) ⇒ (i) and (iii)⇒(i). Note (ii) and (iii) do not imply each other. The global distance rigidity can uniquely determine the shape of a framework, but it is usually difficult to mathematically examine. Infinitesimal distance rigidity can be conveniently examined by a rank condition, but it is not able to ensure a unique shape.

As a comparison:

- The rank condition for infinitesimal distance rigidity requires to distinguish the cases of

and (Theorem 1 in the Basis chapter), while the rank condition for infinitesimal bearing rigidity does not. The proposed infinitesimal bearing rigidity not only can be examined by a rank condition (Theorem 8) but also can ensure the unique shape of a framework (Theorem 10). - An infinitesimally distance rigid framework in a lower dimension may become non-rigid in a higher dimension (see, for example, Figure 6 (b)), while infinitesimal bearing rigidity is invariant to dimensions.

- Although a laman graph embedded in a generic configuration is infinitesimally distance rigid, this result (known as laman’s theorem) is valid merely in 2D spaces. in three or higher dimensions, extra conditions and more edges are required to guarantee distance rigidity. However, in bearing rigidity theory, a laman graph is generically bearing rigid in arbitrary dimensions, and at most

edges would be sufficient to guarantee the bearing rigidity of a framework in an arbitrary dimension. - in the plane(2D),

is the minimum number of edges to ensure infinitesimally distance rigidity. More than edges are required to ensure infinitesimally distance rigidity in three or higher dimensions. As a comparison, in an arbitrary dimension, edges are sufficient to ensure infinitesimal bearing rigidity. less than edges may also be sufficient to ensure infinitesimal bearing rigidity in three or higher dimensions.

| infinitesimal Bearing Rigidity (IBR) | infinitesimal distance Rigidity (IDR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unique geometric pattern | Yes, IBR ensures the unique pattern of a framework. | No, IDR does not ensure the unique pattern of a framework (global distance rigidity does). |

| Rank condition | Yes, IBR corresponds to a rank condition of the bearing rigidity matrix. | Yes, IDR corresponds to a rank condition of the distance rigidity matrix. |

| Invariance to dimension | Yes, a framework that is IBR in a lower dimension remains IBR in a higher dimension. | No, a framework that is IDR in a lower dimension may be flexible in a higher dimension. Universal distance rigidity is invariant to dimensions. |

| Minimum edge number | in an arbitrary dimension, | in the plane, |

| Laman graphs | in an arbitrary dimension, laman graphs mapped to almost all configurations result in IBR frameworks. | in the plane, laman graphs mapped to almost all configurations result in IDR frameworks. A similar result does not exist in higher dimensions. |

Why bearing rigidity has appealing properties in high dimensions can be explained from the perspective of DoF. For example, consider a framework of

As a comparison, when lifted into a higher dimension, the number of independent constraints posed by interneighbor bearings also increases. For example, a bearing in the plane is equivalent to an azimuth angle, whereas a bearing in the 3D space is equivalent to two bearing angles: azimuth and altitude. As a result, the same number of bearings is still able to preserve the bearing rigidity of the framework.

In summary, the bearing rigidity theory possesses a number of attractive features compared to the distance rigidity theory.

Bearing Persistence in Directed Graphs [8]

Notation of Bearing Persistence

The development of bearing persistence is motivated by the bearing-based formation control in directed graphs. The bearing-based formation control problem specifies a set of desired inter-agent bearings,

The bearing Laplacian

For an undirected graph, it is easy to show that

which immediately leads to that, for an undirected formation

In the definition of bearing laplacian matrix, it's claimed that

When the underlying graph is directed, the bearing Laplacian and the bearing rigidity matrix may have different ranks and null spaces.

When the graph is directed, the bearing Laplacian is, however, not symmetric and the above kernel persistence (bearing persistence) relationship would not hold in general.

Definition: Bearing Persistence

A directed formation

The problem of characterizing favourable properties of bearing Laplacian

- The spectrum of

determines the stability properties of the formation system . Preferably, we aim to find conditions to guarantee that has all eigenvalues with non-negative real parts such that the formation system is stable. - The null space of

determines the converged formation shape of the system . Preferably, we aim to find conditions to guarantee such that the converged formation shape is bearing equivalent to the target formation.

Graph conditions to guarantee bearing persistence for a bearing formation still remain open. Here, we will give several graph topological conditions to characterize the spectrum and null space of

A useful formula for

As a counterpart of the matrix expression of bearing Laplacian for undirected graphs, we first derive the following expression of bearing Laplacian for directed graphs. For a bearing formation with a directed graph

where

The bearing Laplacian formula of

The formula of

Theorem 15

For a directed formation

Proof:

Details of

1efine

We remark that, by the property of projection matrix, an alternative formula for

Based on this formula

Theorem 16

For a directed formation

holds if and only if the following two conditions are both satisfied:

(i.e., the formation is infinitesimally bearing rigid), .

Details of Proof

Given Lemma below:

Lemma 12: Null space of matrix product

Consider two matrices

This necessary and sufficient condition follows from the condition of infinitesimally bearing rigidity in Theorem 8 and the null space property of

It is not clear at this stage how to use the second condition, or what it means. In the following sections, we will derive more concrete conditions to characterize the spectrum and null space of

Bearing Persistence in Directed Acyclic Graphs

In this section, we focus on directed acyclic graphs and present several conditions on bearing persistence.

Spectrum of bearing Laplacian: Acycle

The first result characterizes the spectrum property of

Proposition 3

For directed acyclic graphs, the eigenvalues of the bearing Laplacian

Details of Proof

Given two Lemmas below:

Lemma 13: Block triangular matrix

Consider a real-valued block upper triangular square matrix

Lemma 14: Sum of projection matrices

Consider a set of projection matrix,

- For the matrix sum

, if the vectors and are parallel (i.e., linearly dependent), then and is positive semi-definite. - Otherwise, if the vectors

and are linearly independent, then and the matrix sum is positive definite. - For the matrix sum

, if all vectors are parallel, then

- The matrix sum

is positive definite if there exist at least two vectors in the list that are non-parallel.

For directed acyclic graphs, the bearing Laplacian can always be reconstructed (with permutation of vertices and edges) as a block triangular matrix, while the

According to Lemma 12, the set of eigenvalues of a block triangular matrix is the union of eigenvalues of each diagonal block. In this bearing Laplacian, each diagonal block is either a zero block or a positive semi-definite matrix (as a single projection or a sum of projection matrices). Therefore, according to Lemma 13, the eigenvalues of the bearing Laplacian for directed acyclic graphs are real and nonnegative.

Conditions for bearing persistence: Acycle

The following conditions are presented to characterize the null space property of

Proposition 4

For a bearing formation modeled by a directed acyclic graphs, any of the following conditions will result in

- There are at least two vertices that have zero outgoing edge;

- There are at least two vertices with only one out-going edge;

- There are at least two vertices with collinear out-going edges.

Proof:

Due to the block triangular structure of

A special class of acyclic directed graphs is the leader-first-follower (LFF) graph

Definition: Leader-first-follower graph

A leader-first-follower (LFF) graph is a directed graph on

- One vertex (called the leader) has zero out-going edge.

- One vertex (called the first follower) has one outgoing edge and the corresponding edge is incident to the leader.

- Every other vertex has at least two out-going edges and their out-going edges are not collinear.

We now give a sufficient condition for bearing persistence, which characterizes the leader-first-follower (LFF) structure in directed graphs.

Theorem 17

Directed formations over leader-first-follower graphs are bearing equivalent.

Proof: Again, this follows from the block triangular structure of

Bearing Persistence in Directed Graphs Containing Cycles

In this section, we focus on directed graphs containing cycles and derive several necessary and/or sufficient conditions on bearing Laplacian and bearing persistence.

Spectrum of bearing Laplacian: Cycle

For directed graphs that contain cycles, the associated bearing Laplacian (which is asymmetric) cannot be written in a block triangular structure, and thus its eigenvalues are often complex. Thus:

Conjecture 2: The eigenvalues of the bearing Laplacian

of a directed formation have nonnegative real parts.

This conjecture is not true. For counterexamples, see the formation graphs in Figure 10 which will be discussed later. Note that the entries of the bearing Laplacian (and thus its eigenvalue locations) depend on the configurations (agents’ positions). For a given bearing Laplacian associated with a cyclic directed graph and under some special positions, eigenvalues with negative real parts can occur.

Conditions for bearing persistence: Cycle

We first generalize a sufficient condition for characterizing

Proposition 5

For a directed formation

We note that this condition is not necessary. For a counterexample, see the graph (c) in Figure 10. In this example, agent

Now we provide a necessary condition for bearing persistence in directed graphs.

Proposition 6

For a directed bearing formation

Details of Proof

If the underlying directed graph does not contain a spanning tree, then the Laplacian matrix

According to Lemma 12, since the block diagonal matrix

which implies

Proposition 6 provides a necessary condition for bearing persistence that holds for both acyclic and cyclic directed graphs. In particular, Condition (1) in Proposition 4 violates the spanning tree condition, and therefore any bearing formation with two leader agents (i.e., two vertices with zero out-degree) are not bearing equivalent.

Growing bearing equivalent formations

A full characterization of bearing persistence in directed graphs containing cycles still remains an open problem. We now present an alternative characterization to grow bearing equivalent formations, to more number of agents or to a higher-dimensional space.

Proposition 7

Consider a bearing equivalent formation

In particular, if

Details of Proof

Without loss of generality we assign the index ‘n + 1’ to the new vertex p' in the augmented graph G'. The augmented bearing Laplacian L_\mathcal{B}(G') with the augmented graph G' can be expressed by

The condition that the new vertex

This proposition holds for both acyclic and cyclic directed formations, and therefore can be used to analyze complex bearing formations if they can be decomposed by simple sub-graphs consisting of vertices with non-collinear outgoing edges.

The following statement shows that a bearing equivalent formation in a lower-dimensional space will remain bearing equivalent in a higher-dimensional space.

Proposition 8: Dimensional invariance

Bearing persistence is invariant to space dimensions.

This proposition can be seen as a generation of the dimensional invariance property of infinitesimal bearing rigidity.

Examples

Figure 10 shows several examples of bearing equivalent formations modelled by directed graphs with cycles. As a consequence of the cyclic structure in these graphs, their bearing Laplacians have complex eigenvalues. For some special agents’ positions, the associated bearing Laplacian can have eigenvalues with negative real parts.

- For the example of graph (c) in Figure 10, it can be constructed by adding agent

with three out-going edges to agents 1-3-4 in a cyclic triangle formation (which is bearing equivalent). Therefore, the formation of Figure 10(c) is bearing equivalent according to Proposition 7. - For all the bearing equivalent formations evaluated in the 2D space in Figure 10, they remain bearing equivalent when agents’ positions are lifted in the 3-D or higher-dimensional space according to the dimensional invariance property in Proposition 8.

A Unified and General Framework [9]

Preliminaries and Notation

- The

-sphere, i.e., the unit sphere embedded in , is denoted as . We recall that the 1D manifold (corresponding to the unit circle) is isomorphic to the special orthogonal group which can be parametrized by a single angle . - The special orthogonal group

, instead, is not isomorphic to the 2 -sphere , but it holds that . - The Cartesian product

corresponds to the special Euclidean group .

Bearing Rigidity: Definitions and Properties

In this section we introduce the main concepts related to bearing rigidity theory.

Framework Formation Model

Consider a generic formation of

Here, we focus on real world scenarios, nonetheless the definitions and properties provided in the following are valid also for the case

with .

In detail, introducing a global frame common (but not necessarily available) to all the agents in the group, the configuration

Definition: Framework in

A framework embedded in the product differential manifold

The framework model characterizes a formation in terms of the agent configuration, where

Definition: Noncolinear Formation

An

Definition: Homogeneous Formation

An

Note that, for a noncolinear homogeneous

Although the stated assumptions regard the agents state and motion constraints, for a given formation the bearing rigidity properties are related to the bearing vector between neighboring agents. According to the framework model, every edge

Definition: Bearing Function

Given an

Observe that the bearing function determines the shape of the formation in terms of relative pose among all the agents. One of the central questions in bearing rigidity theory is if a given formation with its bearing function uniquely defines the shape. This will explored in the sequel.

Hereafter, the framework model is adopted to refer to an nagent formation (implying

Rigidity Properties of Static Frameworks

Definition of bearing function allows to introduce the first two notions related to bearing rigidity theory, namely, the equivalence and the congruence of different frameworks.

Definition: Bearing Equivalence

Two frameworks

Definition: Bearing Congruence

Two frameworks

Accounting for the preimage under the bearing function, the set

The definition of these sets allows to introduce the (local and global) property of bearing rigidity.

Definition: Bearing Rigidity in

A framework

Definition: Global Bearing Rigidity in

A framework

Proposition 9

A GBR framework

Proof:

For a GBR framework

Rigidity Properties of Dynamic Frameworks

In real-world scenarios, however, agents are generally able to move with or within a formation, and, thus, to change their configuration. Here, the motion constraints are captured by the configuration space

For this reason, in this section we assume to deal with dynamic agent formations, namely formations modeled as frameworks

In this context, we introduce the variation

where

Given this setup, our aim is to identify the conditions under which a given dynamic formation deforms while maintaining its rigidity features, i.e., preserving the existing bearings among the agents over time. The relation between

Definition: Bearing Rigidity Matrix

For a given (dynamic) framework

Indeed,

Nevertheless, one can observe that the null space of $R_\mathcal{B}(\boldsymbol{p}(t)) $ always identifies all the (first-order) deformations of

From a physical perspective, such variations of

Definition: Infinitesimal Variation

For a given (dynamic) framework

It directly results from

In light of Lemma 6, we introduce the notion of trivial variations by considering the infinitesimal variations related to the complete graph

Definition: Trivial Variation

For a given (dynamic) framework

Lemma 6 is fundamental for the next definition that constitutes a key concept in rigidity theory.

Definition: Infinitesimal Bearing Rigidity in

A (dynamic) framework

Otherwise, it is infinitesimally bearing flexible (IBF).

From a physical point of view, a framework

In the rest of the paper, we limit our analysis to the dynamic framework case, and whenever it is possible, the time dependency is dropped out to simplify the notation.

Unified Rigidity Theory

Unlike many of the existing works on the bearing rigidity that begin their analysis with a statement of the agent configuration space and the rigidity results are then derived, not in generic terms, but explicitly as a function of the chosen configuration space. A consequence of this approach is the need to rederive and redefine rigidity concepts.

In this section, we show that stemming from the general setup given in the last section, we are able to unify the study of bearing rigidity that holds for any

The main realization is that any agent can be interpreted as a rigid body acting in 3D space with constraints on its motions (i.e., constrained to move on a differential manifold inside

This approach leads to a general and constructive form for the rigidity matrix and a necessary and sufficient condition relating infinitesimal bearing rigidity to the rank of this matrix.

We consider a formation where each

Independently of

In particular, supposing that the (unit) vectors

This reasoning remains valid for any representation of 3D rotations.

The parameter

In light of the last section, the described formation can be modeled as a framework in

Hence, the directed edge

where

To treat in a unified way multiple domains, we can consider the embedding of each

Hereafter, a superscript

is used to highlight the vectors defined in the lifted spaces.

Observing

where

where

This allows to introduce the following definition.

Definition: Extended Bearing Rigidity Matrix

For a given framework

Note that since

Proposition 10

The extended bearing rigidity matrix can be expressed as

where

are derived from the orthogonal projections of relative position and attitude

and take into account the (time-invariant) matrices defining, respectively, the translational directions of the bearing measurement and -th and -th agents rotation directions in the 3D space with respect to the -th agent frame; are derived from the (time-invariant) incidence matrix of the graph , where .

Details of Proof

According to Definition, the extended bearing rigidity matrix

In light of

where

The table below shows particularization of the structure of the extended bearing matrix in

For any framework embedded in

The embedding of

On one hand, both the infinitesimal and the trivial variations sets can be lifted from

On the other hand, since also the measurements domain

We finally provide a rank condition on the extended bearing rigidity matrix that guarantees the infinitesimal rigidity of the corresponding framework embedded in any

Theorem 18

A non-colinear

Proof:

Because

The table below shows the summary of the principal notions related to bearing rigidity theory for the differential manifolds:

| IBR condition | ||||||

( | ||||||

References

- Section 2-3 of Formation shape control based on bearing rigidity by Tolga Eren in 2012, where

edges in the paper is replaced by here. - Section 2.2-4 of Using angle of arrival (bearing) information for localization in robot frameworks by Tolga Eren in 2007

- Sensor and framework topologies of formations with direction, bearing, and angle information between agents by Tolga Eren, ..., Brian D.O. Anderson

- Section II of Bearing Rigidity and Almost Global Bearing-Only Formation Stabilization by Shiyu Zhao and Daniel Zelazo for the part "arbitary dimensions". Note that the bearing function

is replaced by - Part "BEARING RIGIDITY THEORY" in Bearing rigidity theory and its applications for control and estimation of framework systems: life beyond distance rigidity by Shiyu Zhao and Daniel Zelazo.

- Section 3 of Localizability and distributed protocols for bearing-based framework localization in arbitrary dimensions by Shiyu Zhao and Daniel Zelazo, where the laplacian matrix is represented as

rather than . - Section III of Laman graphs are generically bearing rigid in arbitrary dimensions by Shiyu Zhao etc.

- Characterizing bearing equivalence in directed graphs by Zhiyong Sun, Shiyu Zhao and Daniel Zelazo.

- A unified dissertation on bearing rigidity theory by Giulia Michieletto, Angelo Cenedese and Daniel Zelazo.

We use "framwork" to replace the "network"; use

to replace .