Introduction of Linear algebra

This is the note from MNE8108 Engineering Methods in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, CityU (semester A, 2025)

Contents mostly From Linear Algebra by Arnold J. Insel etc.

Appendix A: Sets

Definitions

Definition: sets

collection of objects, called elements of the set

- list them using

- no order:

subsets:

- proper set:

- empty set:

calculation

union:

intersection:

- disjoint sets:

- disjoint sets:

finite sets:

infinite sets:

Number systems:

- Natural number:

- Integral number:

- Rational number:

- Real number:

- Complex number:

Cardinal number: the number if elements of a set

For infinite sets:

- Countable sets:

: - Uncountable sets: beth one:

operations

operation: from a set to itself

Unary:

- negation:

- factorial:

- trigonometric:

Binary:

tenary: ...

Arithmetic

Set Elements Operation Closure Associative Commutative Distributive - - Set Elements Operation Identity inverses or

More generally:

| Set | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | |||

| Operation | |||

| Closure | |||

| Associative | |||

| Commutative | |||

| Distributive | - | - | - |

| Identity | |||

| inverses |

group

Given:

- Set of elements

- Operation:

| Set | |

|---|---|

| Elements | |

| Operation | |

| Closure | |

| Associative | |

| Commutative | |

| Distributive | - |

| Identity | |

| inverses |

- If communtative: commutative group / abelian group

- If not commutative: non-commutative group / non-abelian group

Example of group:

commutative:

with commutes under

non-commutative:

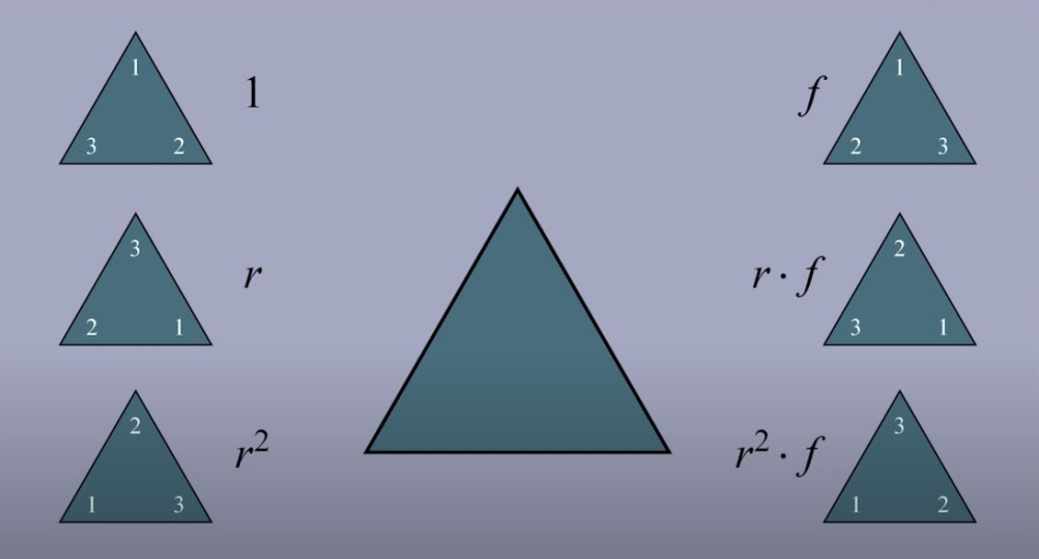

- Dihedral group:

: rotation : reflection

- Dihedral group:

Ring

Given:

- Set of elements

- Operation:

| Set | ||

|---|---|---|

| Elements | ||

| Operation | Addition | Multiplication |

| Closure | ||

| Associative | ||

| Commutative | ||

| Distributive | ||

| Identity | ||

| Inverses |

- distributive: left distributive v.s. right distributive

- If communitative, just check one distributivity

Example of ring:

- commutative:

with

- non-commutative:

with matrix addition and matrix multiplication

Appendix C: Fields

Given:

- Set of elements

- Operation:

| Set | |

|---|---|

| Elements | |

| Operation | Addition |

| Closure | |

| Associative | |

| Commutative | |

| Distributive | |

| Identity | |

| inverses |

Example of field:

with with with , a finite field with two elements(0,1); operations: XOR + AND.

Modulo Arithmetic:

Theorem C.1 (Cancellation Laws)

- If

, then - If

, then

Corollary

the identity elements and the inverse elements are unique

Theorem C.2

1.2 vector space

Given:

- Set of elements

- Operation:

- Commutative group

under , with a Field

| Set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | ||||

| Operation | Addition | Scalar multiplication | Addition | Multiplication |

| Closure | ||||

| Associative | ||||

| Commutative | ||||

| Distributive | - | |||

| Identity | ||||

| inverses |

Definition: vector space

A vector space

(Commutativity of addition); (Associativity for each ); - There exists an element in

denoted by s.t. ; , there exists an element , s.t. ; ; ; ;

Module definition: similar to vector space, but:

- commutative of scalar multiplication not required

- commutative of multiplication for number part, not required

Definition

- sum:

- product:

- scalars: elements of

- vectors: elements of vector space

- n-tuple:

elements of a field in this form: - entries / components:

- 2 n-tuples are equal if

: set of all n-tuples with entries from a field - vectors in

: column vectors

- entries / components:

Definition about some vector spaces

Definitions: Matrix

- diagonal entries:

with - i-th row:

- j-th column:

- zero matrix: all zero

- square: the number of rows and columns are equal

- equal:

- set of all

matrices with entries from a field is a vector space:

matrix addition:

Definitions: function

Let

for each

Definitions: polynominal

- coefficient:

- zero polynominal:

- degree:

for zero polynominal - largest exponent of

- equal if equal degree and

When

addition and scalar multiplication:

set of all polynominal:

Theorem 1.1: Cancellation Law for Vector Addition

If

Corolloary 1

The vector

Corolloary 2

The inverse element of vector is unique (additive inverse)

Theorem 1.2

In any vector space

1.3 subspace

Definition: subspace

A subset

In any vector space

Theorem 1.3(subspace)[core]

Let

. whenever and . whenever and .

Examples

matrix

The transpose

A symmetric matrix is a matrix

- Clearly, a symmetric matrix must be square. The set

of all symmetric matrices in is a subspace of since the conditions of Theorem 1.3 hold

A diagonal matrix is a

- the set of diagonal matrices is a subspace of

polynominal

Let

is a subspace of

theorem and definition

Theorem1.4

Any intersecton of subspaces of a vector space

Definitions

sum of nonempty subsets

direct sum:

are subspaces of

1.4 linear combination and systems of linear equations

Definition: linear combination

Let

Observe that in any vector space

Definition: span

Let

In

Theorem 1.5(span and subspace)

- The span of any subset

of a vector space is a subspace of . - Any subspace of

that contains must also contain the span of

Definition: generate

A subset

1.5 linear dependence and linear independence

Definition: linear independent

A subset

In this case we also say that the vectors of

For any vectors

Thus, for a set to be linearly dependent, there must exists a nontrivial representation of

Consequently, any subset of a vector space that contains the zero vector is linearly dependent because

Definition: linearly independent

A subset

The following facts about linearly independent sets are true in any vector space:

- The empty set is linearly independent, for linearly dependent sets must be nonempty.

- A set consisting of a single nonzero vector is linearly independent. For if

is linearly dependent. then for some nonzero scalar . Thus

- A set is linearly independent iff the only representations of

as linear combinations of its vectors are trivial representations

Examples

polynominal

For

is linearly independent in

theorem

Theorem 1.6

Let

linearly dependent, then

Corollary

Let

Theorem 1.7

Let

1.6 bases and dimension

basis

Definition: basis [core]

A basis

Examples

Recalling that

and is linearly independent, we see that is a basis for the zero vector space. In

, let is readily seen to be a basis for

and is called the standard basis for . In

, let denote the matrix whose only nonzero entry is a in the ith row and jth column. Then is a basis for . In

the set is a basis. We call this basis the standard basis for .

Theorem

Theorem 1.8:

Let

for unique scalars

Theorem 1.9

If a vector space

Theorem 1.10(Replacement Theorem)

Let

Corollary 1

Let

dimension

Definitions: dimension [core]

A vector space is called finite-dimensional if it has a basis consisting of a finite number of vectors. The unique number of vectors in each basis for

Examples

- The vector space

has dimension - The vector space

has dimension - The vector space

has dimension - The vector space

has dimension

The following examples show that the dimension of a vector space depends on its field of scalars.

- Over the field of complex numbers, the vector space of complex numbers has dimension

. (A basis is .) - Over the field of real numbers, the vector space of complex numbers has dimension

. (A basis is )

Corollary and theorem

Corollary 2

Let

- Any finite generating set for

contains at least vectors, and a generating set for that contains exactly vectors is a basis for . - Any linearly independent subset of

that contains exactly is vectors is a basis for . - Every linearly independent subset of

can be extended to a basis for .

Theorem 1.11:

Let

Examples

The set of diagonal

where

Corollary

If